Campaign

The history of Europe in the 23 years following the French Revolution records an extraordinary series

of military campaigns and shifting alliances.

Although no attempt has been made to parallel the Napoleonic wars, this period of history has been

used as the inspiration for the game “Campaign”.

When there are four players, alliances can be made — and broken — from the start. With three players,

alliances should only be made against a third force that is threatening to dominate the game.

In order to help players to earn the game "Campaign" two sets of rules have been prepared.

Napoleon Bonaparte set out to dominate the Continent,

thereby producing opposing coalitions that at different times involved almost every country in Europe

and at times included Russia.

A brief resumé of those fascinating years is given in the accompanying

folder.

Each player sets out to be a “Napoleon” and to win

the game by the outright defeat of his opponents or by the acquisition of large areas of territory.

When

only two players are involved there can, of course, be no alliances.

Players

are advised to start by playing to the Introductory game rules and when they have mastered this

version, they can more easily follow the additional rules governing the full, Standard game.

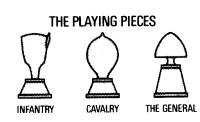

| Contents | The Playing Pieces |

|---|---|

| Playing board: 4 sets of playing pieces, in different colours, comprising 1 General, 9 infantry and 9 cavalry units; 6 sets of 4 Town Cards of different colours; 4 Alliance Cards; 2 dice. |

|

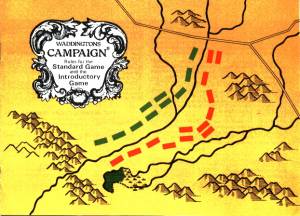

The Board

This is a representation of Europe and western Russia, giving six areas of approximately equal size. These areas are — France, Prussia, Russia, Austria. Italy and Spain.Each country has four provincial towns, five of them have Capital cities. France and Prussia are the same colour but these two countries are never used together as bases in the same game. Italy is never used as a base.

In the centre is an area corresponding to the central European mountain range — other features, sea and forests, are used to provide obstacles to troop movements and to denote national boundaries.

Playing pieces may not move on to or over any square that is marked as sea, forest or mountain. They are only allowed to move from one country into another by crossing the frontier rivers or the red, frontier lines.

THE INTRODUCTORY GAME

1. Preparation

For 4 players

The four countries used as bases are France, Russia, Austria and Spain. Prussia is not used as a base.

Place the Generals on the Capital squares of matching colour. Place 4 infantry and 4 cavalry pieces on the starting squares indicated on each side of the Generals. Extra pieces should be left, easily accessible, in the box.

Distribute the Town and Alliance cards Each player will begin with the five cards of his own colour in front of him for all to see. The Prussia and Italy cards are placed in any convenient space near the board.

Throughout the game all the Town and Alliance cards must be easily visible to all the players.

For 3 players

Players may select any one country as their base — the game will develop differently according to

which ones they choose. An obvious choice would be Spain. Prussia and Austria but other combinations

are possible.

France and Prussia cannot be used as base countries at the same time.

For 2 players

Each player controls two armies. Players may divide the countries between them in any way they

wish.

____France and Spain__v__Russia and Austria

_or France and Russia__v__Spain and Austria

_or France and Austria__v__Spain and Russia

France and Prussia cannot be used as base countries at the same time.

2. The dice

The two dice are always thrown together at each player’s turn.They are used only to move the pieces, they are not used to determine the outcome of an attack.

The dice throw may be used to move just one, or several pieces. For example, with a throw of 7 a

player can move one piece 7 times.

7 pieces once each or make any combination of moves that totals

7.

Players are not compelled to use the full dice throw.

3. Movement of the pieces

Although the luck of the dice throw can vitally affect the game, it is essential that players understand fully how the playing pieces are moved and how attacks must be planned if they are to be successful.The General

This piece moves one square at a time, in any direction, horizontafly, vertically or diagonally.

It can therefore attack from any direction.

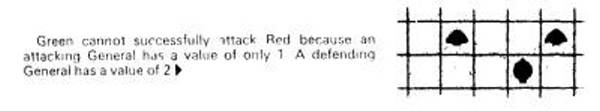

When it is attacking it has a value of 1 — when it is

defending it has a value of 2.

This is the only piece that can capture a town — by simply moving on to it.

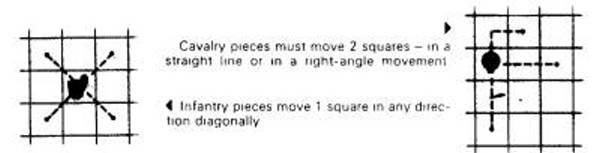

Cavalry These pieces must move two squares at a time. They can only move horizontally or vertically — never diagonally.

Infantry ,br>These pieces move only one square at a time. They only move diagonally.

Pieces may not jump over one another. Only one piece may occupy any one square.

4. Breakthroughs

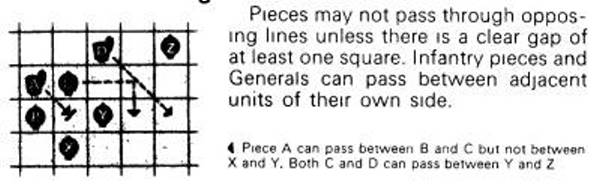

Pieces may not pass through opposing lines unless there is a clear gap of at least one square. Infantry pieces and Generals can pass between adjacent units of their own side.

Piece A can pass between B and C but not between X and Y. Both C and D can pass between Y and Z.

5. The Cards

There are two kinds of Town cards; twelve have a red circle, the other twelve have a yellow circle.When any town, of either colour, is captured, the corresponding Town card is claimed. The player keeps the card until the town is captured by another player, when it must be surrendered.

The Alliance cards are simply used as evidence that two players have entered into an alliance — and each player will hold the card of his ally.

6. Capturing Towns

Only a General can capture a town - simply by moving on to the Town square. It must remain there until the next turn. When a town is captured, at the end of the turn the player claims the Town card.Pieces attacked and defeated are removed from the board at the end of the turn (See Section 10).

The Alliance may be broken by either player at any time during the game by simply announcing his

intention and taking back his Alliance card.

It is perfectly legitimate for a player to plan secretly to attack his declared ally but he may not

break the alliance and attack his former ally in the same turn.

The first player throws both dice and moves whatever pieces he wishes — up to the total of his dice

throw. For example, with a throw of 7 he can move 1 piece 7 times. 7 pieces once each, or he can

make any combination of moves that total 7.

The player on his left then takes his turn, and so on round the board.

Pieces can only attack along a line in which they are allowed to move.

When attacking. all pieces, including Generals, have a value of 1.

When defending, all pieces except Generals, have a value of 1. The General, when defending has a

value of 2, ie, it takes 3 pieces, or 2 pieces and a General to capture another General.

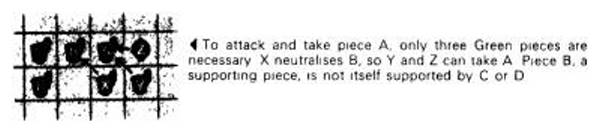

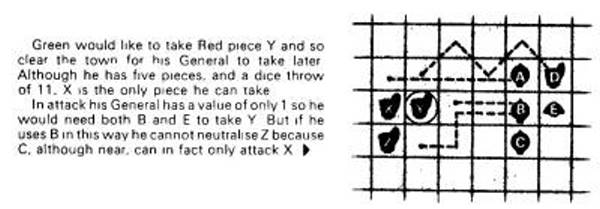

Examine the following examples carefully so that the “attack” rules are fully understood.

When working out their attacking moves, players are not allowed to move pieces, let go and pick

them up again. Once a piece has been moved and let go it must not be touched again in that turn.

Allied forces may act as closely as they wish. Opposing pieces can be taken by any mixed, allied

force.

Infantry and cavalry pieces successfully attacked must be removed from the board and returned to

the box. Captured Generals are not removed from the board.

The player with the defeated General misses his next turn. Having missed one turn he may re-enter

play in the usual way He may not be attacked again until after this second turn.

In case no decisive victory is achieved it is advisable to set a time limit for the end of the

game. The player holding the largest number of towns when the deadline is reached would be the

winner.

It is assumed that at the start of the game the red towns in a player’s own country are already

“occupied” by him and he has the troop units in his army.

It is important to remember that playing pieces gained by taking towns are lost again immediately

the towns are taken by another player.

If a player takes an opposing piece, and in the same turn his General is able to move on to a

red-circle Town square, at the end of his turn he will remove one piece — but at the same time

he will gain a piece and the player losing the town will lose another piece.

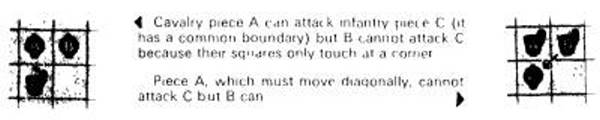

To attack. infantry pieces must be touching at a corner, cavalry pieces must be touching along the

side and the General can be in either position.

Allied forces may act as closely as they wish in supporting each other’s troops.

If some or all of the remaining troops are “tied” to towns they will almost certainly be quickly

lost as other players re-capture the towns.

He is allowed to recruit one new cavalry or infantry piece (he may choose which) if he has only —

He is allowed to recruit one cavalry and one infantry piece if he has only —

If he holds more than four of either infantry or cavalry pieces (there is only space for 4 of each

on the board) he must bring any additional units into the Enlistment Area when earlier units have

been moved away towards the capital.

No other player may attack the Capital or any pieces being mobilised until mobilisation is complete

— ie. every possible piece is on a correct starting square.

Napoleon was born in Corsica in 1769 but was sent to receive a military education at the army

cadet school in Paris.

The turning-point came in 1796 when, after important services to the revolutionary government,

Napoleon was appointed to the command of the French army in Italy.

The other European powers became alarmed at the declared doctrines of the French revolutionaries

and at the threat of increasing French domination.

Now Napoleon moved southwards to defeat the Austrians in a series of campaigns in Italy and soon

the Coalition collapsed.

Within months of the highly successful conclusion of the war in Italy, Napoleon was planning

an attack on the British Empire in India by way of Egypt.

At this time he fully realised that for success he needed further victories abroad and stability

mixed with reform at home. Accordingly, during 1800 he waged a brilliant campaign in Italy, where

he inflicted another crushing defeat on the Austrians.

He recovered all the Italian territory and claimed yet more before signing a peace treaty in

1801.

During this period, Napoleon was able to devote most of his time to the re-organisation of the

government of France, and in 1804 he was proclaimed Emperor.

Meanwhile, Anglo-French hostilities broke out again and Napoleon raised an army of 200,000 men

ready to invade England.

Yet Napoleon still planned a decisive attack on the Continental Powers.

In these circumstances war began again and in a storming campaign Napoleon won a series of

brilliant victories and made himself master of central Europe.

By the end of 1807 the Napoleonic Empire had reached its zenith but from then onwards the structure

began to crack.

In spite of the appalling losses of men and material in Russia, Napoleon still succeeded in

raising new armies - but with increasing difficulty.

He was sent into exile on the island of Elba but escaped a year later and returned to France

where, such was the power of his name, he was quickly able to gather his former troops about him.

As a general, Napoleon took full advantage of all the main military developments of his time.

To learn even a little of the history of the Napoleonic wars is usually to wish to know more.

The following books are recommended for those who would like to widen their knowledge of those

turbulent years.

Players cannot, therefore, attack and remove a piece from a Town square — and capture the town -

in the same turn.

7. Capturing a Capital

A Capital can only be taken after all the provincial towns in that country have been captured and

are still held. When this happens the defeated player is out of the game.

8. Alliances

To make an alliance, players simply agree to be allies and then exchange Alliance cards. A player

must not cross any border into his ally’s territory without his consent.

He must declare his intention to

break the alliance (taking back his Alliance card) during one turn, and attack at his next turn.

This gives his former ally one clear turn to re-deploy his forces if he wishes.

9. Commencing play

Decide the order of play by. in turn, throwing both dice. The player with the highest score will

begin.

10. Attack and defence Back

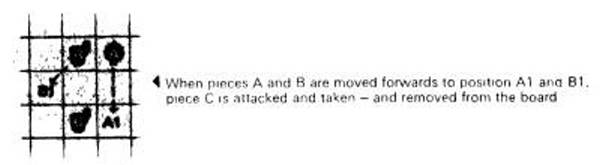

An infantry or cavalry piece is attacked and taken — and is removed from the board — when superior

forces are positioned on adjacent squares.

An attacking piece does not move on to the square of

the piece it is attacking.

Only one piece may be attacked in any one turn. The attacking player must say which piece it is

he is attacking and he may not change his target once he has made a move A defeated piece is

removed from the board at the end of the turn.

To attack, infantry pieces must be touching at a corner, cavalry pieces must be touching along the

side and the General can be in either position.

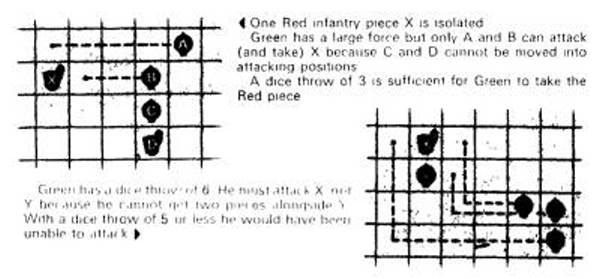

11. Examples of attacking moves

It is Important to note that even with a high dice throw and a heavy troop concentration it may

still be impossible to capture an opposing piece because the attacking troops cannot be moved into

correct attacking positions.

12. Capturing a General

When a General is taken, at the end of the turn it must be moved immediately to its starting position

on the Capital square.

At the same time all remaining troop pieces must be moved to their appropriate

Capital starting squares.

Winning the Game

The game is won outright by the player who either:—

1. captures all his opponents’ Capitals.

2. captures 8 towns, of whatever colour, but not including the 4 in his own country. He still

wins the game even if his own 4 provincial towns have been lost to his opponents.

Losing the game

A campaign is lost — and the player is out of the gamewhen :—

1. he loses his Capital

2. he is left with a General but no troops.

THE STANDARD GAME

13. Additional troops

In the Standard game the "red" towns have a new significance.

When a player captures a “red” town,

at the end of the turn he takes the corresponding Town card and he also claims one infantry or

cavalry piece, according to the symbol shown in the circle.

He mayplace this extra piece on any

empty square adjacent to the Town square.

At the same time the player who previously held the Town

card must remove from the board a corresponding infantry or cavalry piece of his own.

He must take

the piece that is closest to the town just captured.

If the losing player does not have a correct

piece he must discard an incorrect one.

14. Supporting pieces

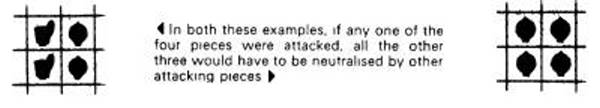

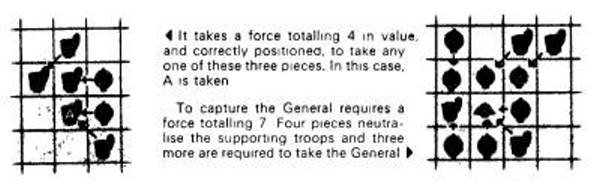

A piece being attacked is supported by any other pieces adjacent to it.

Therefore, ,before a piece

can be taken, every adjacent piece must be “engaged” (and so, neutralised) by an attacking piece

of equal value.

A closely-grouped force can, therefore, be very difficult to attack — as were the

“squares” of the period.

Only one piece chosen for attack can be supported. Supporting pieces cannot themselves be supported.

Remember — To support, pieces of all kinds have only to be adjacent.

15. Capturing a General

When a General is taken, provided it has one or more troop pieces still left, it is moved immediately

to the square indicated in the “Enlistment Area” of its own country.

Any troops remaining to it,

wherever they may be, are also moved immediately to the same Enlistment Area.

Therefore, a player whose General has Just been captured

is given the opportunity of recruiting more troops.

a. 1 troop piece and no red Town cards

or b. 1 troop piece more than red Town cards in his possession.

a. an equal number of troop pieces and red Town cards

or b. more red Town cards than troop pieces.

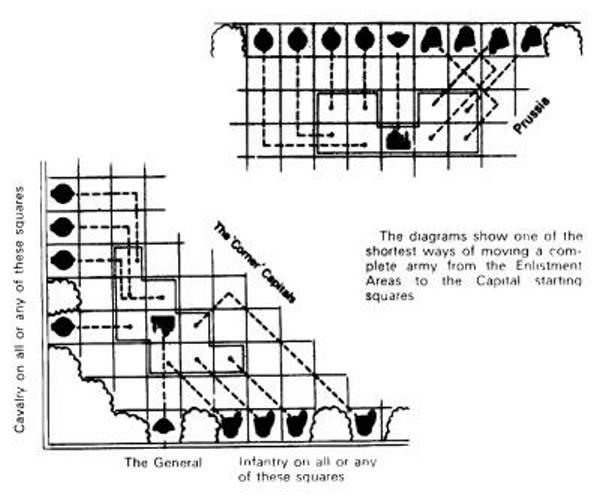

16. Re-entering play

Before a "new" General and his army may engage in hostilities they must “mobilise” in the Capital.

The player must therefore use his next few turns to move his army from the Enlistment Area on to

the correct Capital starting squares.

As soon as all pieces are on the starting squares, or all possible starting squares are occupied

(supposing there are more than 4 infantry and/or cavalry pieces) at the following turn they can

be moved off as at the start of the game.

As players become more experienced they will recognise the parallels between the moves they make

and the military and political strategies of the Napoleonic years — the strength of the closely

grouped force, but the slowness of its movement, the quick successes of the very light force, but

its vulnerability to sudden counter attack, the need of allies when menaced by a skilful (and

perhaps lucky) opponent, but the need to keep open a line, of retreat should the ally prove

untrustworthy.... "Campaign" is a game to be studied as well as played.

© 1971 John Waddington Ltd.,

Castle Gate, Oulton, Leeds LS26 8HG

The Years of Napoleon

The period of history which inspired the development of the game "Campaign" was one dominated

by Napoleon Bonaparte.

There he had a distinguished career and as a result became a captain at

the age of twenty.

Although he welcomed the outbreak of the Revolution in France in 1789 he was

at first very little involved in either political or military affairs, but the outbreak of wars

in and after 1792 between France and the main European powers gave the young officer his chance.

By this time the politicians

were convinced that Napoleon was the only French military leader who was likely to carry out an

offensive strategy successfully.

They were not disappointed. To contemporaries, Napoleon's Italian

campaigns "seemed almost miraculous; a dozen victories in as many months, announced in bulletins

which struck the public like thunderclaps".

To meet this threat the first of a number of

Coalitions was formed, between Austria, Britain, the Netherlands, Piedmont, Prussia and Spain.

France declared war on this Coalition and three years later had over-run Belgium, the Netherlands

and all Germany west of the Rhine, at which point Prussia and Spain made peace.

Austria made peace, ceding further territory in Belgium, Germany and in

Italy.

But not all the victories were the work of Napoleon - other French leaders had their successes.

Indeed, Napoleon actually left Europe in 1798 for a campaign much further east.

He landed there in 1798 and gained a

quick and overwhelming success on land.

However, while he was occupied in Egypt and later in Palestine,

the French suffered reverses both at sea and in Europe.

These defeats resulted from the formation

of a Second Coalition created by Austria, Bavaria, Naples, Portugal and Turkey, The Forces of this

group achieved initial victories, driving the French out of Italy and into Switzerland.

The British

now united with Russia in an attack on the French-held Netherlands but without success.

The French

beat them off and the Tsar withdrew from the Coalition.

Napoleon decided to return home secretly,

found himself a national hero, planned a coup d'etat and took power as First Consul.

With the northern

pressure off, he again turned south.

This was the end of the Second Coalition. It left Britain alone harassing the French by

mounting a blockade of French-controlled ports.

This blockade, however, also damaged the trade of

many other European countries with the result that a new alliance was formed, led by Russia and

aimed against Britain, known as the League of Armed Neutrality.

This confrontation culminated in

a victory for Nelson over the Danish fleet at the battle of Copenhagen.

The French troops were kept waiting for two years for a favourable opportunity,

but the invasion threat was finally removed by Nelson's victory over the combined French and Spanish

fleets at Trafalgar.

Responding to the threat,

Russia, Prussia and Austria joined Britain in another defensive alliance - the Austrians were

especially hostile to Napoleon's decision to make himself king of Italy in 1805.

In a series of shifting alliances,

Napoleon at one time persuaded the Prussians to declare war on Britain, and later, after another

defeat of the Russians, he had Tsar Alexander as an ally.

Now he was faced with policing almost the whole of the Continent.

He was also intent

in preventing any British trade with the rest of Europe and this meant guarding the entire coastline.

The Spanish and Portuguese coasts, however, he did not protect. The Spaniards, now in revolt against

France, appealed to Britain for help and British forces were landed in Portugal.

A series of

indecisive engagements followed and Napoleon's armies became enmeshed in a slow war of attrition,

quite different from the previous pattern of events.

Then, in 1810 Napoleon's armies moved into

Russia in order to forestall a possible counter-attack by the Russians who were uneasy about the

presence of French troops along their borders.

In a huge army of 600,000 men were many units of

Austrians, Italians and Prussians.

The Napoleonic armies struck deep into the heart of the Russian

Empire but the delaying tactics of the Russians, and the severity of winter, turned the French

invasion into a disaster which culminated in the famous 'retreat from Moscow' in 1812. By 1811 the

British, under General Wellesley, were achieving notable successes and in 1814 his troops crossed

the French border.

Also, by this time the European Powers had

at last learned the need for co-ordination of military effort.

As a result they invaded France

itself, taking advantage of the country's comparative military weakness after the defeat in Russia.

In 1814 the Allies took Paris and Napoleon was forced to abdicate.

But his return to power was shortlived.

Characteristically he marched to meet the British and

Prussian armies but he was finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815, captured and sent to exile on

the lonely island of St. Helena, where he died in 1821.

His soldiers were armed with a new, more efficient flintlock musket and improved field artillery.

Their movements were carried out with great speed and dash, for he was a great believer in rapid

mobility and in flexibility of manoeuvre.

In the field he tried to concentrate his fire-power on

decisive points, and he effectively combined his artillery and infantry, which moved in smaller

formations than had been usual before his time.

He was a master of feint attacks and of attacks

on isolated bodies of the enemy from a central position.

Above all Napoleon was always quick to

take advantage of the mistakes of his opponents and he always tried to act on his belief in the

superiority of offensive over defensive warfare.

These principles and practices can be discerned

in his first major campaign, in Italy, and he never departed from them, Indeed, towards the end

of his life he said, "I have fought sixty battles and I have learnt nothing which I did not know

in the beginning."

The consistency of his methods was matched by that of his success.

F.M.H. MARKHAM: Napoleon.

ELIZABETH LONGFORD: Wellington: The Years of the Sword

N.HAMPSON: The First European Revolution: 1776—1815.